The following is an edited and revised version of my undergraduate honors thesis at Northwestern University, originally written in 1998. A list of the footnoted sources for this essay can be found here.

Introduction

2001: A Space Odyssey was released in the tumultuous spring of 1968, at the same time that Americans were reeling from President Lyndon Johnson’s announcement that he would not seek reelection and the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. It might seem odd that so many people would get so excited about a science fiction movie in the midst of urban race riots and campus protests against the Vietnam War, but to many, 2001 had far greater importance than its sci-fi trappings. Baffling early audiences with its non-traditional structure, theme, and presentation, the film was soon embraced by many members of a younger generation entranced by its consciousness-raising message and its psychedelic special effects. Over the next 30 years, the film would not only become a part of American culture, but would eventually be hailed as a masterpiece of modern cinema.

An examination of 2001’s appeal over the last three decades provides insight into the changing perceptions of a single cultural document over time. Young Baby Boomers were initially attracted to the film for very different reasons than those of audiences in the ’80s, 90s, and beyond. Because 2001 is unlike many other films in that it invites its viewers to apply their own subjective interpretations, it serves particularly well as a signpost for contemporary social attitudes and trends. Examining the different ways that 2001 has been interpreted by its audience over that time, reveals a great deal about evolving cultural attitudes toward issues such as technology, spirituality, and the commercialization of American society.

2001: A Space Odyssey was the third biggest box office hit of 1968 (after Mike Nichols’ The Graduate and William Wyler’s Funny Girl) and, upon the completion of its initial theatrical run, was one of the top twenty grossing movies of all time.[1] Over the next 30 years it would go on to gross over $56.7 million in the United States and $190.7 million worldwide.[2] Science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke’s companion novel of the same name has sold over four million copies worldwide,[3] and his three follow-up novels to the story all spent several weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. One of these sequels was turned into a moderately successful film, 2010: The Year We Make Contact, released nearly 15 years after 2001. Audiences, critics, and filmmakers consistently rank the film among the 100 best ever made. Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert has stated that if asked which films would still be familiar to audiences 200 years from now, he would select 2001, The Wizard of Oz, Casablanca, and Star Wars as his first choices.[4]

Like other popular works of science fiction, such as Star Trek and the Star Wars movie trilogy, 2001 is constantly referenced in popular culture. Films as diverse as Woody Allen’s Sleeper and Jan DeBont’s Speed have featured homages to 2001. The film’s theme music, taken from Richard Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathrustra, has been heard everywhere from the opening notes of Elvis Presley’s 1970s Las Vegas lounge act to car commercials. Music videos have featured costumes and sets directly inspired by the film. Dozens of fan websites exist on the Internet, where the film’s enthusiasts present and debate their differing theories about its meaning.

Why is 2001 still so popular after so long? Its box office success alone is insufficient to explain why there are so many 2001 fans, many of whom were not even born when the film was released. Neither does its status as a science fiction film guarantee a continuing audience of sci-fi “groupies” – many other science fiction movies that enjoyed success on their initial run have failed to maintain their popularity.

The key to 2001’s appeal lies in examining how the film has been interpreted, defined, and redefined over the past three decades. Because 2001, unlike most popular films, can be said to have a fluid meaning, different audiences have applied their own subjective interpretations to it. In addition, 2001’s two primary authors have over the years actively continued to indoctrinate audiences with their own differing interpretations. By placing these interpretations in the context of the different times in which they were made, the answers to how and why 2001 has become a part of our mass cultural consciousness become more clear.

The Space Race and the Decline of Hollywood

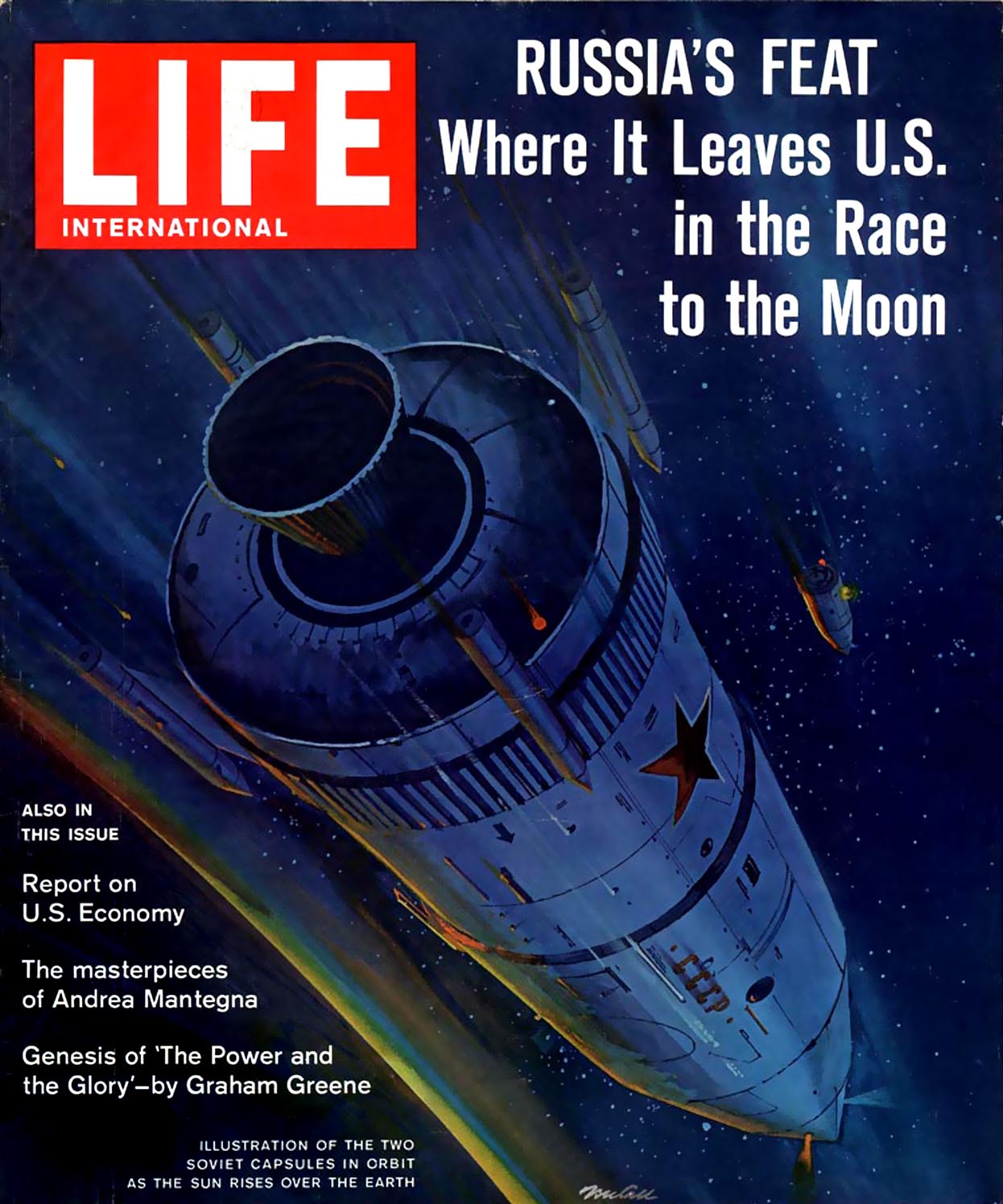

It is important to understand the far-reaching appeal of the 1960s space race not only because it contributed to the reasons 2001 was made, but also because it established a frame for the for the film’s initial release. On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy gave one of his most memorable and influential speeches, calling for the United States to land a man on the moon before the end of the decade. Having been humiliated by the Soviet Union in their attempts to launch an astronaut into orbit, the young National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was committed to winning the race to the moon, no matter what the financial cost. The American public not only eagerly followed every launch but also made the young men of the astronaut corps national heroes. Hundreds of thousands of people were directly involved in making the components and devices that would be necessary to perform the Herculean task of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.

At the same time, American film studios were going through a transition that played a key role in the production and initial release of 2001. The introduction of television in the 1950s, the collapse of the studio system following the 1948 Paramount antitrust decrees, and the creative stagnation caused by the blacklisting of many actors and screenwriters had dealt a serious blow to the prestige of American cinema. Many studios took enormous gambles during the 1950s and 1960s, spending lots of money on experimental widescreen and color technology that would allow them to create big screen epics far larger in scale than anything television could offer. Some, like Ben-Hur, Dr. Zhivago, and The Sound of Music were fantastic successes; others, like Cleopatra and The Fall of the Roman Empire, were tremendous failures. By 1970, various corporate conglomerates had bought out most of the major studios, ultimately shifting their emphasis toward profit making and away from artistic expression. For a brief time during the mid-Sixties, however, studios in transition often encouraged filmmakers to experiment with different techniques in an attempt to capture a rapidly changing audience.

By the middle of the 1960s, members of the Baby Boomer generation began to have great clout in Hollywood. Bonnie and Clyde, starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway, was one of the first films of the era to achieve success among an primarily youth audience. The success of Bonnie and Clyde was nothing, however, compared to that of Mike Nichol’s The Graduate, which upon its initial release in December 1967, became one of the top ten domestic box office grossing films of all time. Starring Dustin Hoffman as a disenchanted college graduate who has an affair with the older wife of one of his parents’ friends, the film was one of the first articulations of the generation gap to make its way to the silver screen. The fresh young Baby Boomer audience not only exerted tremendous power over the box office, but also over critical expectations as a new generation of film critics began to enter the mainstream.

Kubrick and Clarke

It was during this time of transition that director Stanley Kubrick established himself as a major force in American filmmaking. One of Hollywood’s most enigmatic personalities, Kubrick was a young filmmaker from the Bronx who had independently financed his first two features before drawing the attention of United Artists, where he completed two more films (The Killing and Paths of Glory) that scored critical, if not financial success. In 1960, he was selected to fill in for Anthony Mann to direct Kirk Douglas’ production of Spartacus. Kubrick then directed a film version of Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial novel, Lolita. He finally received both critical and commercial success in 1964 with a Cold War satire entitled Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. Only two weeks after Dr. Strangelove was released, Kubrick had already decided that his next project would be about outer space. A film publicist from Columbia Pictures who was a close friend of Arthur C. Clarke urged Kubrick to contact the British science fiction writer, who had lived in Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon) since the mid-1950s.[5]

Clarke had been interested in technology since his boyhood days, when he started tinkering with electronics and crystal radios. During World War II, Clarke worked on developing radio equipment for the British Air Force, and after the war, he became Chairman of the British Interplanetary Society. He began writing both science fiction and non-fiction “extrapolations” of the future, and his 1956 short story “The Star” won him a Hugo award from the World Science Fiction Society. His novels, such as Childhood’s End and The City and the Stars, are primarily concerned with technology and the transformation of mankind into some more advanced form of life. Already scheduled to fly to New York to promote Man and Space for Time-Life, Clarke accepted Kubrick’s invitation, and the two began to discuss various ideas for the proposed film.[6]

Kubrick and Clarke planned to develop the 2001 story first as a novel, and then adapt a screenplay for the film. In practice, the novel and screenplay ended up being written almost simultaneously. Throughout 1964, Kubrick and Clarke continued brainstorming and writing, with Clarke doing almost all of the writing from his room at New York’s Hotel Chelsea. By the end of the year they had come up with enough of a manuscript to sell the idea to MGM.[7]

Once the world’s largest and most profitable motion picture studio, MGM suffered greatly during the 1960s. The once-great lion of Hollywood was surrounded on every side by unhappy shareholders and creditors hoping to purchase and dismantle the company. Robert O’Brien, the studio’s chief executive, had faith in Kubrick’s vision, and gave him almost unlimited license and control over the production of 2001.[8] In the experimental environment of the mid-1960s, MGM was willing to give a director who had proven that he could be commercially successful the chance to create the first “grown-up” science fiction epic. Using Kubrick and 2001 as an example, film industry analyst James Monaco wrote, “The rules of the game had changed, as had the players. And for a few years, since no one knew what the new rules were, there was a genuine sense of freshness.”[9] In February of 1965, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer announced that they would finance the production of a science fiction film tentatively titled Journey Beyond the Stars. The film was budgeted at $6 million and was supposed to take two years to make. It would actually be another three years and $10.5 million before 2001 was finally released.[10]

Production

Throughout the spring of 1965, Clarke continued to flesh out the novel, while Kubrick began setting up arrangements for production. After taking a vacation in Ceylon, Clarke flew to England, where Kubrick had already begun pre-production in August 1965 at Borehamwood Studios. With some plot details still not completely worked out, Kubrick began shooting on December 29, 1965. Clarke finished his first draft of the novel in April 1966, and immediately approached Kubrick about publication, since they had agreed that the novel should come out before the film. Kubrick offered several modifications to the novel that kept Clarke busy for several more weeks, then refused to sign the contract that had been worked out with Delacorte Publishing, claiming that the manuscript still needed work. This upset Clarke greatly, especially since the book had already been set in type and Delacorte had taken out a two-page advertisement in Publisher’s Weekly. He began to lose faith in the project, making the following entry in his diary in the summer of 1966:

July 19. Almost all memory of the weeks of work at the Hotel Chelsea seems to have been obliterated, and there are versions of the book that I can hardly remember. I’ve lost count (fortunately) of the revisions and blind alleys. It’s all rather depressing – I only hope the final result is worth it.[11]

It would not be until July 1968, three months after the release of the film, that Clarke’s novel would see publication, though the version finally approved by Kubrick differed very little from that he had written two years earlier. Although the two always had nothing but kind words to say for each other after the project was completed, at least one reviewer has speculated, “from the known characteristics of both men, their partnership was artistically rather less unified than the colored publicity brochures allow.”[12]

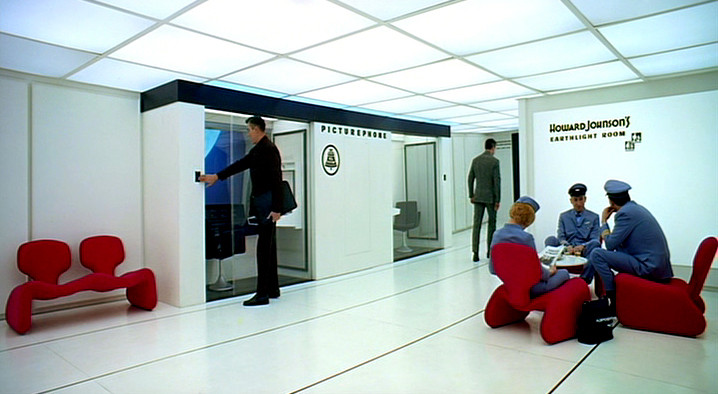

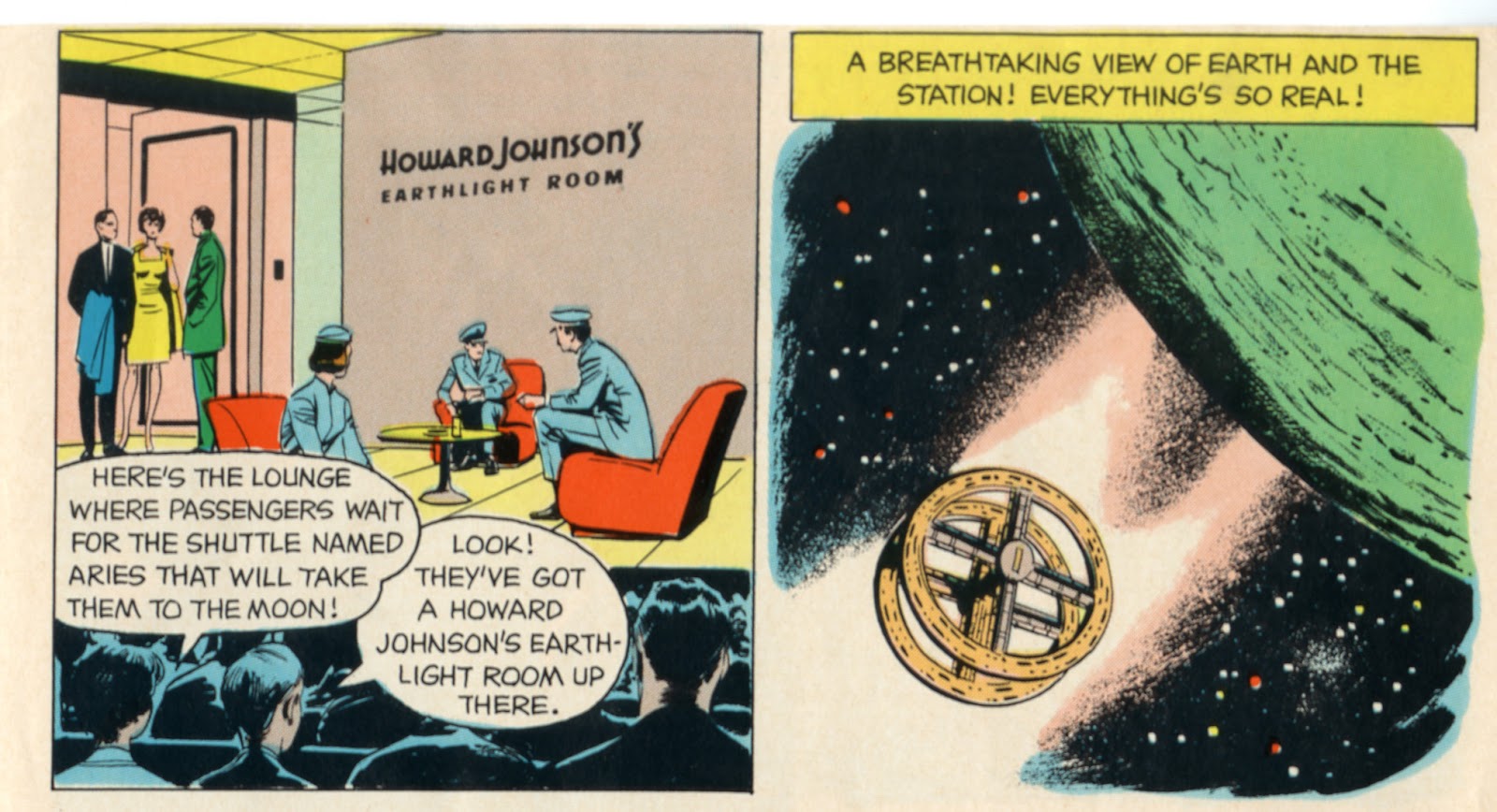

On the recommendation of Clarke, Kubrick hired space consultants Frederick Ordway and Harry Lange, who had assisted some of the major contractors in the aerospace industry and NASA with developing advanced space vehicle concepts, as technical advisors on the film. Ordway was able to convince dozens of corporations such as IBM, Honeywell, Boeing, General Dynamics, Grumman, Bell Telephone, and General Electric that participating in the production of 2001 would generate good publicity for them. Many companies provided copious amounts of documentation and hardware prototypes in return for “product placements” in the completed film. They believed that the film would serve as a big-screen advertisement for space technology. When IBM learned that the plot involved a murderous computer however, they ordered that their trademark be removed from many of the sets.

Every detail of the production design, down to the most insignificant elements, was designed with technological and scientific accuracy in mind. Senior NASA Apollo administrator George Mueller and astronaut Deke Slayton are said to have dubbed 2001’s production facilities “NASA East” after seeing all of the hardware and documentation lying around the studio.[13] It is no small credit to the research of Kubrick’s production crew that most audiences and critics still find 2001’s props and spaceships more convincing than those seen in many later science fiction movies.

During the production and post-production of 2001, which lasted into the spring of 1968, the world outside of Borehamwood Studios was changing rapidly. The patriotic enthusiasm of the Space Race soon gave way to the “confirmed kills” and body bags of Vietnam. On college campuses around the country, students began to question the authority of their schools and government, and began to organize in support of such causes as civil rights and ending the war. For the most part however, the outside world did not intrude upon the relatively isolated production of 2001.

Critical Reactions

2001 was finally released in April 1968, accompanied by great hoopla and excitement. As a 70mm Super Panavision spectacular, 2001 was a prestige picture promoted on the same level as such films as Lawrence of Arabia and How the West Was Won. In major markets, 2001 was offered with advanced booking and reserved seating, and the picture was promoted as “an epic drama of adventure and exploration”. Publicity materials featured the technology portrayed in the film, like space stations and moon bases, and played up its scientific realism.[14] Early audiences consisted mainly of the oldern and more affluent people that traditionally went to prestige pictures. Unlike earlier Cinerama spectaculars however, 2001 lacked a traditional Hollywood plot structure, dialogue, or resolution. It made little or no attempt to explain things to the audience; rather it presented images, sound, and music in a way that made little sense to many present.

The film begins four million years ago at the “Dawn of Man”. In the prehistoric African savanna, a mysterious black monolith appears, prompting our distant ape ancestors to learn how to use the first tools to kill for food. Cutting to the near future, the audience follows Dr. Heywood Floyd, a bureaucratic space scientist, as he takes a routine trip to the Moon. It is revealed that a four million-year-old monolith has been discovered in a lunar crater. When exposed to the light of the sun, the monolith sends out a powerful electronic signal. The film then skips ahead eighteen months, to the first manned space mission to Jupiter. The ship’s human astronauts, Dave Bowman and Frank Poole, are forced to consider disconnecting the super-intelligent HAL 9000 computer that runs their ship when it makes an error. Learning of this, the computer succeeds in killing everyone but Dave, who disconnects it and finds out about the previously secret discovery of the lunar monolith. Arriving at Jupiter, Dave discovers another black monolith orbiting the gas giant. Flying into it, he experiences a fantastical 23-minute light show before landing in a Louis XVI style decorated room. There he ages rapidly before encountering the final monolith, which turns him into a newborn “Star Child” and returns him to look at the planet Earth from orbit.

After press screenings on April 1 and 2, the film premiered in New York City on April 3, 1968. Despite MGM’s aggressive promotion of the film with taglines like, “the most technically complex movie ever made,” and, “you’ve never seen anything like it,”[15] its unconventionality shocked and surprised even the most experienced critics. Roger Ebert reports that at the Los Angeles premiere on April 4, Rock Hudson stormed out of the Pantages Theater asking, “Will someone tell me what the hell this is about?”[16] As Alexander Walker wrote in his 1971 book, Stanley Kubrick Directs, “2001 reached its initial audience slightly in advance of their expectations; acceptance of the film’s radical structure and revolutionary content was slower to come. The first wave of critics wrote mixed reviews. While seeing a new use of film, they reacted with responses geared to conventionally shaped films.”[17]

The most common complaint of early press reviews of 2001 was its long length and slow pace. Not counting overture, entr’acte, and walkout music, the film was approximately 161 minutes long. Due to its slow and deliberate pace, it seemed much longer for many audience members. New York Times critic Renata Adler noted that “people on all sides when I saw it were talking throughout the film.” Joseph Morgenstern of Newsweek described parts of the film as a “crashing bore,”[26] and Arthur Schlesigner Jr., declared it “morally pretentious, intellectually obscure, and inordinately long.”[27]

Kubrick was “confused and puzzled” over the difficulty and lack of understanding reported by early audiences. After the Los Angeles premiere, Kubrick decided to tighten the film. With editor Ray Lovejoy, he cut approximately 19 minutes of footage, including a montage of life aboard the Discovery and an entire sequence detailing the preparation for Poole’s EVA. Title cards were added before the “Jupiter Mission – 18 Months Later” and the “Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite” segments, and a brief shot of the monolith was added to the “Dawn of Man” segment to better orient audiences.[28] Arguing that he did not believe the trims made a crucial difference and only affected some “marginal people,” Kubrick contended, “it does take a few runnings to decide finally how long things should be, especially scenes which do not have narrative enhancement as their guide.”[29] Kubrick’s goal was to make the film more accessible to the preview and press screening audiences, the vast majority of whom were between the ages of 35 and 60. It is questionable whether these changes would have made any difference to the younger people who eventually became the film’s core audience.

While most critics found 2001 merely confusing or boring, some of the most renowned film theorists of the time gave it almost universally negative reviews. Andrew Sarris, a critic and film theorist generally “more concerned with the director’s attitude toward the spectacle than the spectacle itself,” was irked by Kubrick’s detached style of directing. In his initial review for the Village Voice on April 11, 1968, he dismissed 2001 as “a thoroughly uninteresting failure and the most damning demonstration yet of Stanley Kubrick’s inability to tell a story coherently and with a consistent point of view.”

Although Pauline Kael publicly clashed with Sarris on several occasions, she shared his disdain for 2001, describing it as “trash masquerading as art.” In an essay entitled “Trash, Art, and the Movies,” Kael called the film “monumentally unimaginative” and “the biggest amateur movie of them all.” Her writings about 2001 make numerous references to its appeal among the counterculture and the “tribes” of youth who watched it under the influence of illegal substances.

Stanley Kaufman argued that the content of a film, as characterized by its script, performances, and technical merit, is far more important than stylistic “stunts, camera techniques, and cutting.”[18] Although 2001’s special effects impressed Kaufman, he argued that Kubrick had overemphasized them at the expense of the plot, dialogue, and acting. He argued stated that Kubrick’s obsession with both the technology of the film and the future had “numbed his formerly keen feeling for attention span.” Kaufman summarized his review by saying that “in the first 30 seconds, this film gets off on the wrong foot and, although there are some amusing spots, it never recovers. Because this is a major effort by an important director, it is a major disappointment.”[19]

While the more conservative East Coast critics gave some of the most negative reviews, 2001 was received well by reviewers on the West Coast. Gene Youngblood wrote an enthusiastic review for the Los Angeles Free Press entitled “2001: A Masterpiece.” In his 1970 book, Expanded Cinema, he devoted two chapters to the film and declared it an “epochal achievement of cinema”.[20] Similarly, Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called 2001 “a milestone, a landmark for a spacemark, [sic] in the art of film.” Despite his annoyance at the ambiguous ending, he argued that even that “cannot really compromise Kubrick’s epic achievement, his mastery of the techniques of screen sight and screen sound to create impact and illusion.”[21]

Young film critics on college campuses around the country had a lot of positive things to say about 2001. Both the Harvard Crimson and the University of Wisconsin’s Daily Cardinal published eight-page reviews, some of the longest they had ever published. The Crimson’s review, written by Tim Hunter, Stephen Kaplan, and Peter Jaszi, was so comprehensive that it was reprinted in the journal Film Heritage. Focusing not on the film’s technological achievements and special effects, which most of the favorable mainstream reviews had done, the Harvard students looked instead at the film’s themes of death, dehumanization, and the importance of mankind’s evolutionary and technological progression. In doing so, they went so far as to take issue with Arthur Clarke’s assessment of Bowman’s journey as “the end of an Ahab-like quest on the part of men driven to seek the outer reaches of the universe.” Instead, they argued that the death and rebirth of Bowman as the Star Child is part of a cyclical progression. In their final analysis, they acknowledged that it might be a few years before the wonder of the film’s special effects wears off before 2001 can be objectively judged.[22]

In light of the positive response 2001 was receiving from mass audiences and other reviewers, some critics who had given the film a negative review went to see it a second time. Free from the initial shock and prepared for its unconventionality, many took a closer look and decided to recant and publish positive reviews. As one author put it, “accompanying this truly popular response came the more or less public realigning of some critical opinions and even in a few cases downright recanting.”[23]

Both Kubrick and Clarke responded to the critical reception of 2001 with the argument that it did not really matter what critics said, so long as the general public found the film stimulating and engaging. When Playboy asked Kubrick how he accounted for the negative reviews of Renata Adler, Andrew Sarris, and others, he responded that almost all of the hostile reviews were from New York critics. He had some very harsh words for his hometown reviewers, saying that “perhaps there is a certain element of the lumpen literati that is so dogmatically atheist and materialist and Earth-bound that it finds the grandeur of space and the myriad mysteries of cosmic intelligence anathema.” He minimized their impact, however, pointing out that although it was a crass way to evaluate one’s work, 2001 was on its way to becoming one of the most commercially successful films in MGM’s history.[24] Arthur Clarke was more direct when he wrote, “as for that dwindling minority who still don’t like it, that’s their problem, not ours. Stanley and I are laughing all the way to the bank.” He argued that the reevaluation by some critics was simply a normal reaction to “a new and revolutionary form of art”, and that those who remained hostile probably did so because they had difficulty facing the film’s religious implications.[25]

Commercial Success

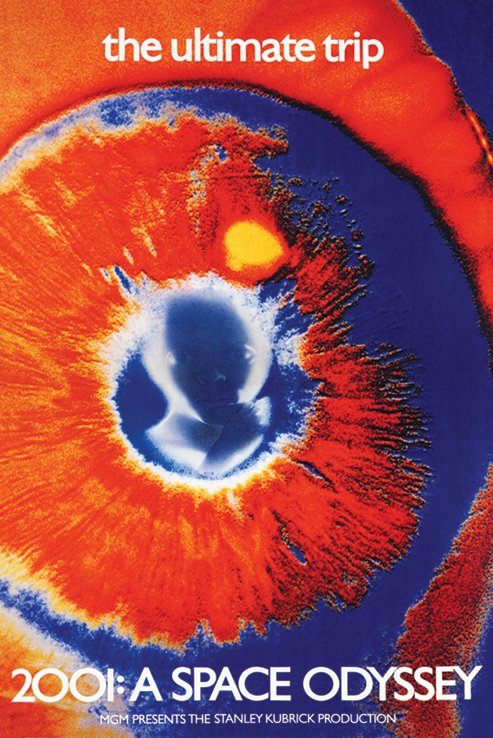

The fear of many theater owners that 2001 would be a commercial catastrophe because of its lack of advance bookings was soon quelled when large numbers of college-age moviegoers made cash purchases on the day of screening. As word about the film spread, many people went to see 2001 again and again. Arthur Clarke’s oft-repeated motto on the press junket that “If you understand 2001 on the first viewing, we will have failed”[30] played right into MGM’s new strategy of marketing the film toward a youth audience. The second round of publicity for the film focused much more on its psychedelic aspects, and the advertising slogan was changed from “An epic drama of adventure and exploration” to “The Ultimate Trip.”[31]

In its initial release, 2001 played at some theaters for over a year and a half. It ran 79 weeks at the Pacific Cinerama Dome Theater in Hollywood, California. It was canceled in the middle of a profitable New York run in late 1968 because MGM wanted to get Ice Station Zebra, the Cold War thriller starring Rock Hudson and Ernest Borgnine, out in time for Christmas. 2001 had a very profitable re-release in the summer of 1974, and a new crop of young fans, many who had been too young to see the film when it first came out were born.

Youth Appeal

Kubrick and MGM apparently failed to anticipate the extent that 2001 would catch on among the youth audience. Kubrick wanted the film to appeal to a mass audience in the hopes of providing intellectual stimulation. In a 1968 interview for Playboy magazine he stated, “I think if 2001 succeeds at all, it is in reaching a wide spectrum of people who would not often give a thought to man’s destiny, his role in the cosmos and his relationship to higher forms of life.”[32]

These early viewers described 2001 as unlike any other film they had seen. In the 70mm Cinerama format, the curved screen wrapped slightly around the audience, drawing them into the picture. The unusual musical choices made by Kubrick, his use of ambient sounds like breathing and heartbeats, and the fantastic special effects light show overwhelmed the senses of many. As one college-age audience member recalled the reaction of one of this friends after seeing the film for the first time, “He had to wait huffing and shaking in the car with his head on the dash board for several minutes before he could start the engine.”[33] Another wrote a letter to Kubrick, saying, “My pupils are still dilated, and my breathing sounds like your soundtrack. I don’t know if this poor brain will survive another work of the magnitude of 2001, but it will die (perhaps more accurately ‘go nova’) happily if given the opportunity.”[34] For these people, 2001 became much more than a movie.

2001 as Religious Experience

Many described the film as a religious experience, saying that it opened up new doors for them in their spiritual lives. One audience member who first saw the film at the age of seven recalled how 2001 filled the place of religion for him, saying, “My family was atheist and I had no religion as a child. The realm of ideas was given a somewhat exalted status as I grew up around dinner table discussions of philosophy, astrophysics (layman level), and the universe. But certainly there’s a great human capacity, perhaps need, for wonder and awe, and in that way 2001 filled the gap for my “Godless” upbringing.”[35] As another letter-writer wrote to Kubrick, “I would not be at all afraid to state that with 2001 you may have quite possibly saved any number of spiritual and physical lives. For it is within the power of a film such as yours to give people a reason to go on living – to give them the courage to go on living.”[36] Others used language reminiscent of “born again” Christians, like the person who wrote Kubrick, “Your movie has given me many moments which I seek out in my life – moments of feeling alive. After your movie one thought kept coming back into my mind. It is one that I have had many times, but which seemed more clear than ever now; how many times must I be born to realize what I am.”[37] At one screening of the film in Los Angeles, a young audience member rose to his feet at the film’s conclusion, ran down the aisle and crashed through the screen, all the while shouting, “It’s God! It’s God!”[38]

Counterculture

The members of the counterculture were another group of people who drew inspiration from 2001. Legions of young hippies went to theaters carrying blankets and sat down on the floor between the first row of seats and the screen, “turning on, tuning in, and dropping out” with marijuana, LSD, and other substances to the long special effects sequence at the movie’s end. Both Arthur Clarke and Stanley Kubrick have denied using any illegal substances during the writing or production of 2001, although Clarke points out that this may have been the case for some members of the art and special effects departments. Some of the first film shot for the movie in 1965 was from the “psychedelic” Star Gate segment, but most of the special effects were added in 1967 and early 1968 during post-production.[39]

While staying at the Chelsea Hotel, Clarke did seek inspiration from the company of beat writers Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs, but there is no evidence that he participated in any of their well-documented experiments with illegal drugs. The science fiction author has described himself as being “only mildly in favor of the death penalty even for tobacco peddling.” At a science fiction convention shortly after the film’s premiere, one anonymous fan passed him a packet of cocaine, along with a note that this was “the best stuff.” Clarke says that he promptly flushed his gift down the toilet.[40] Similarly, Kubrick disavowed the use of drugs, arguing that “the artist’s transcendence must be within his own work; he should not impose any artificial barriers between himself and his subconscious.”[41]

Anecdotes about drug use should not distract, however, from the vast number of young people who went to see the film with more critical motivations in mind. A Toronto theater owner noted that many young people came to see the film over and over again, but said that he had not noticed any drug use and that if he did, he would “put a stop to it in a hurry.”[42]

2001 as Satire

Many early fans of 2001 responded to what they perceived as its satire of future society. The film’s depiction of travel to an orbiting space station and the moon is filled with corporate logos, trademarks, and other “product placements” for companies such as IBM, Pan Am, Howard Johnson’s, and AT&T. As Mark Crispin Miller, a professor of film and media studies at Johns Hopkins University, wrote:

The world of Doctor Floyd (like the new dorm, mall or hospital) is a world absolutely managed – the force controlling it discreetly advertised by the US flag with which the scientist often shares the frame throughout his “excellent speech” at Clavius and also by the corporate logos – “Hilton”, “Howard Johnson”, “Bell”- that appear throughout the space station. In 1968, the prospect of such total management seemed sinister – a patent circumvention of democracy.[43]

The fact that almost all of the human dialogue in the film was bland, dry, and meaningless was seen by many to be a satirical commentary on the futility of the spoken word. F.A. Macklin points out that many critics missed this satire inherent in the films use of inept language. He argues that space scientist Heywood Floyd “is the character who brings out the most obvious satire, not black this time as in Kubrick’s Lolita or Dr. Strangelove, but a revealing of the wretched decline of language, so close to our own present jargon and conversation that the critics took it as a bad script by Clarke and Kubrick.”[44] An audience member recalls, “While many criticized it for its low-key dialogue (“Did you have a nice flight?” is about as passionate as it gets), others say [sic] that far from poor writing, lines like that brilliantly reveal the mind-numbing and de-personalizing effects of too much technology.”[45]

The non-traditional critical reception of 2001 definitely played a large part in securing its place in the American cultural consciousness. The sheer amount of material that was published about the film far exceeded that of more mainstream “respectable” cinema, and drew attention to it not only from the mainstream media, but also from various academic and trade journals, where debates about the value of 2001 continued for several months. The battles between various film scholars also highlighted the generation gap and the growing power of younger audiences and critics, who seemed to connect with the film better than more seasoned veterans. Continued criticism over the next three decades would reveal that different audiences seemed to connect with 2001 often for very different and contradictory reasons.

Effect on Baby Boomers

Years later, many Baby Boomers who first saw 2001 in the theater at a young age have said that it was a major influence in their lives. As members of a generation searching for meaning and identity, the film’s cosmic questions resonated deeply with many. One viewer recalled, “I felt some connection with the film…some weird hopeful thing that climaxed when the Star Child made its appearance on the screen at the end. I remember going to bed that night after the movie unable to get that image out of my mind…and knew in that 14-year-old way that something had shifted for me in life.”[46] Filmmakers, artists, engineers, and early computer technicians all have credited the film for giving them direction in life and the motivation to aspire to their chosen careers.

Some people were motivated to pursue filmmaking. Actor-director Tom Hanks has said that his first viewing of the film at the age of 12 was an experience that allowed him to appreciate the power of movies.[47] Director James Cameron has said, “2001 meant a great deal to me when I was 16 or 17 years old and it sparked my interest in filmmaking.”[48]

Other people found inspiration in the film’s portrayal of futuristic technology. One electronics engineer recalled, “When I started college in 1974, I remember having my roommate drive me to a theatre that was running 2001, where I sat through four showings at a time, every weekend. As a result, I determined that I would do something technology related.”[49] Software developer Stephen Wolfram said that as a nine-year-old, he was impressed by the film’s futuristic technology, and Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates has said that 2001 inspired his vision of the potential of computers.[50]

Many others saw their horizons expanded beyond already existing interests. Geoffrey Alexander first saw the film on his ninth birthday. He writes, “While I’ve never lost interest in science, I knew after that my focus in life would really be more on those mysteries…that my favorite studies would become art, religion, philosophy, and (of course) poetry, literature, and film…and that, whatever the medium or form, I would be an artist.” Alexander, who maintains The Kubrick Site, one of the Internet’s most comprehensive websites on Stanley Kubrick, speculates about the film’s appeal to Sixties youth:

To those who came upon it back in the mid-sixties – having seen absolutely nothing like the realities (real or imagined) it depicts – the mythical and metaphorical implications (which aren’t shallow to begin with) were even more powerfully communicated. Especially to young people who, unlike many adults, are not burdened with assimilating the experience into some complex of preconceptions.

Perhaps 2001 is truly, and most significantly, a film about youth – on an archetypal, indeed mythical level – and age, and it’s destiny (certainly the way in which the film portrays the ‘maturity’ of the species is cautionary). That’s all quite emblematic of the Sixties…and how suitably ironic it is that this film about ‘the future’ should arguably be the most significant and representative film of its particular era.[51]

While many of the Baby Boomers immediately identified some of 2001’s darker themes, it took several viewings for some young audience members to catch some of the film’s pessimistic elements. While most immediately caught the irony and satire of the film’s portrayal of a future dominated by corporations and technology, their appraisal of the film’s assessment of humanity was more mixed. One person, who first saw the film as a teenager, wrote 30 years later, “I felt 2001 was an optimistic film…aside from the jabs at technology and such. It was only later that I saw the ‘dark side’ of it all…my first dozen viewings or so were through the untainted eyes of a 14-year old.”[52]

Authorship of 2001

The question of the authorship of 2001 is one that would come to dominate discussion of the film in later years. Depending on whether or not one accepted Kubrick or Clarke as his or her source, the answers one found to the film’s profound questions could be quite different. Most Kubrick fans tended to play up the story’s dark and satirical elements, while Clarke’s followers felt that it was more optimistic, particularly in its use of technology.

Most critics and film scholars saw the film as belonging almost exclusively to Stanley Kubrick. Considered by many to be the embodiment of the American auteur director, Kubrick maintained tight control over the production and presentation of his films. As one of the early commentators on 2001’s technical merits wrote, “In its larger dimension, the production may be regarded as a prime example of the auteur approach to filmmaking…In this case, there is not the slightest doubt that Stanley Kubrick is that author. It is his film. On every 70mm frame, his imagination, his technical skill, his taste, and his creative artistry are evident.”[53]

Because Clarke had little involvement in the further development of the story after Kubrick began production on the film, his novel differed from the cinematic version in several significant ways. In Clarke’s story, the astronauts travel to Saturn, not Jupiter, and the ending scenes are somewhat different from the way in which they appeared in the film. Clarke’s novel provided far more exposition, and explained the backgrounds of Heywood Floyd, Dave Bowman, and Frank Poole. He added a Cold War subplot about an orbital nuclear weapons platform, and explained HAL’s malfunction as a result of human error, something that he felt the film needed.[54] Science fiction critic John Hollow compared the cinematic and literary versions of HAL, concluding, “The Hal in the book is betrayed by his human partners. He is given two messages by Mission Control and at the same time has never been programmed to lie. The resulting conflict, a sort of giant short circuit, drives him crazy.” Many saw the 2001 novel as far more optimistic than the film, including Hollow, who wrote, “2001 the novel….is not about the revolt of the machines, but about the two things Clarke seems to think we mortals would most like to know in a universe in which we can only hope that the odds are in favor of the race’s survival: that we are not alone and that we have not lived in vain.”[55]

Clarke did get to see some footage from the film that was shot in 1966, although his book was finished before the end of the film’s production. Kubrick’s delay in approving the novel for publication had caused Clarke great consternation. Still, the two displayed a united front in promoting the film’s release. Clarke gave almost all of the credit for the story to his collaborator, saying that, “2001 reflects about ninety percent on the imagination of Kubrick, about five percent on the genius of the special effects people, and perhaps five percent on my contribution.”[56] In 1972, he characterized his novel in the same terms as a review of the film, saying “You will find my interpretation in the novel; it is not necessarily Kubrick’s. Nor is his necessarily the “right” one – whatever that means.”[57]

Clarke’s Book

Many people who found Kubrick’s movie confusing purchased Clarke’s book in the hope that it would illuminate them to the real meaning of the film. Physicist Freeman Dyson, who was filmed for an unused “documentary-style” prologue to the film, wrote that he found the book “gripping and intellectually satisfying, full of the tension and clarity which the movie lacks. All the parts of the movie that are vague and unintelligible, especially the beginning and the end, become clear and convincing in the book.”[58]

Others have pointed out that although the novel and film may share the same story, the “spirit” of the film had nothing to do with Clarke and everything to do with Kubrick. One reviewer noted that the novel restored this Clarkean spirit “with such a rush that it read like a parody of his themes and confirmed my suspicion that in the film Kubrick had, to a certain extent, frozen him out.”[59] One writer noted, “Obviously, the novel differs from the film radically in emphasis and even basic conception, but at times Clarke’s explanations throw light upon the film, if only through contrast.”[60] Another found a more convoluted answer, “As far as 2001 is literature, as far as it could exist, as it does, in the form of the novel, even if there were no film, it is Clarke’s work. As far is it is film, and could exist, even if there were no book, it is Kubrick’s.”[61]

Many noted that the problem may lie in the fact that the novel relied on words to transmit its message, while the film relied on the futility of language. Kubrick shares this view, pointing out one striking example:

At one point in the film, Dr. Floyd is asked where he’s going. And he says, ‘I’m going to Clavius’, which is a lunar crater. Then there are about fifteen shots of the moon following this statement, and we see Floyd going to the moon. But one critic was confused because he thought Floyd was going to some planet named Clavius. I’ve asked a lot of kids, ‘Do you know where this man went?’ And they all replied: ‘He went to the moon.’ And when I asked, ‘How did you know that?’ They all said: ‘Because we saw it.’ [62]

Kubrick suggests that as a visual experience, 2001 is intensely subjective and cannot be objectively explained, much like one cannot “explain” a Beethoven symphony.[63] In a 1969 interview, he said, “…in a film like 2001, where each viewer brings his own emotions and perceptions to bear on the subject matter, a certain degree of ambiguity is valuable, because it allows the audience to ‘fill in’ the visual experience themselves.”[64] Paraphrasing Marshall McLuhan, the director contended that “in 2001, the message is the medium” rather than words.[65]

As people who make their living through the usage of words, the reaction of many science fiction writers to the cinematic 2001 was, not surprisingly, rather hostile. Ray Bradbury harshly criticized Kubrick’s treatment of the story at the same time that he praised Arthur C. Clarke. “Clarke, a voyager to the stars, is forced to carry the now inexplicably dull director Kubrick the albatross on his shoulders through an interminable journey of almost thee hours.”[66] Many who had gotten their start in the “Golden Age” of science fiction under the tutelage of esteemed editor and author John W. Campbell, were dismayed by the sharp turn that the genre took in the 1960s. Instead of focusing on the possibilities of science and technology, many “New Wave” writers increasingly focused on issues like religion and spirituality. Many older writers did not see this as science fiction at all, but as fantasy. They saw Kubrick’s film as taking Clarke’s hard science fiction masterpiece and turning it into another New Wave spiritual tale. Like many of the critics, their expectations did not meet the final result. Campbell claimed that “2001 departed from Clarke’s original ending – an encounter with a truly superior race – to wander in an LSD trip of fantasies.” Lester del Rey wrote, “This isn’t a normal science-fiction movie at all, you see. It’s the first of the New Wave-Thing movies, with the usual empty symbolism. The New Thing advocates were exulting over it as a mind-blowing experience. It takes very little to blow some minds. But for the rest of us, it’s a disaster.”[67] Robert Heinlein, however, who was one of the first “Golden Age” science fiction writers to include New Wave themes in his writings, did list 2001, along with Things to Come and The Time Machine among his list of science fiction films that he particularly admired.[68]

Books

Shortly after 2001’s release, several major camps had formed around its interpretation. One was made up of the fans of Kubrick, who saw 2001 as a clever satire on the arrogance of humanity, a theme which was also apparent in other Kubrick films such as Dr. Strangelove and A Clockwork Orange. Another consisted of those who followed Arthur Clarke’s novel as the definitive text for understanding 2001. A third group argued that it was impossible to interpret the film, since it was first and foremost an experience and thus beyond criticism. In the early 1970s, different books were published about 2001 that came from very different perspectives. It has been speculated by some that Kubrick masterminded the publication of at the first three of these works in an attempt to help audiences who had difficulty understanding the film without help.[69]

The Making of Kubrick’s 2001, which came out in 1970, was edited together by Jerome Agel, who is best known for his collaborations with Marshall McLuhan on The Medium is the Massage and War and Peace in the Global Village. This paperback collection is clearly intended for the youthful fans of the film; Agel’s name appears at the beginning of the book accompanied by the inscription, “Sun in Gemini, Moon in Aries, Cancer Rising”. Produced with the assistance of Kubrick, Clarke, and other members of the production staff, it contains published articles, reviews, and interviews, excerpts and random facts, a ninety-six-page photo insert, and an extensive collection of letters written to Kubrick about the film. Writer Don Daniels refered to Agel’s book as the “Holy Writ” of the 2001 cult but complained about how this “anti-anthology” replaces coherence with accumulation.[70] The Making of Kubrick’s 2001, despite its title, contains far fewer details about the actual production of the film as it does about the way it was “made” in the eyes of the public and the critics.

Alexander Walker’s Stanley Kubrick Directs, published a year later for more critically-minded audiences, examines the entire body of Kubrick’s work and is based extensively on interviews that the critic had with the director, a longtime friend of his. The chapter dealing with 2001 focuses on the film’s visual appeal, satire, and the moral ambiguity of the final scenes. It refers to some of the differences between the film and the book, specifically the role of the early monolith as a teaching device and the orbiting nuclear bombs, as items that were discarded by Kubrick in later drafts of the script. Alexander’s book quotes Kubrick saying that the banal dialogue of Dr. Floyd and the other space scientists in the film is what he believed “the way the people concerned would talk.”[71]

The Lost Worlds of 2001 was published in 1972 by Arthur C. Clarke. It contains stories about his collaboration developing the novel and screenplay with Kubrick, as well as many leftover “chapters” from the early versions of his novel. Although Clarke begins the book by saying that he is concerned not with the development of the film, but that that of the novel, “regarded as an independent and self-contained work”, much of the work deals with the frustration that he suffered because of the constant rewrites demanded by Kubrick. Some of the unused material Clarke includes involves an extra-terrestrial named “Clindar” who studies and teaches the early ape-men, the Earth-based training of the Discovery astronauts, and alternate versions of the story’s Star Gate sequence. Most of the book is in such fragmented form that it contains little that would prove enlightening to any but the most ardent fans of Clarke’s novel.[72]

After the mid-70s, the amount of literature published about 2001 slowed to a trickle. One author, writing in 1978, cited the film’s cult appeal as a cause for this “de facto moratorium on 2001 criticism.” Because even the most enlightened commentators found themselves unable to verbalize the powerful experience the film provided, he argued that many had taken the position that it was “ultimately, for some reason, an uninterpretable film.”[73]

Influence on Other Films

Before 2001, the genre of science fiction cinema had been characterized by poorly written, low-budget “B” grade features with titles like Radar Men From the Moon and Teenagers from Outer Space. A very small number of “A” level features, like Forbidden Planet and The War of the Worlds stood out from the rest, but before the mid-1960s, most studios had been reluctant to spend large amounts of time and money on what they considered to be “Buck Rogers” adventures for children.

2001’s impact on other science fiction films did not become apparent for several years, but was quite profound. Other films about space travel released during the late 1960s paled in comparison to 2001. Robert Altman’s Countdown, a story about the race to land an astronaut on the Moon, became irrelevant within a year of its release and John Sturges’ Academy Award-winning Marooned, released in 1969, also soon faded from the public memory. To some, like French critic Michel Ciment, it seemed as though, “Kubrick has conceived a film which in one stroke has made the whole science fiction cinema obsolete.”[74]

After the July 1969 Apollo moon landing public interest in the space program began to wane. America had beaten the Soviets to the moon and fulfilled John F. Kennedy’s goal. As the Vietnam War drained more resources from the American economy and American’s became more interested in spending money on matters closer to home, interest in the space program waned. Science fiction movies became less interested in scientific extrapolation, and more interested in down-to-earth stories, like The Planet of the Apes and its sequels, which were largely commentaries on the environment and the use of nuclear weapons. Other films, like THX-1138, Soylent Green, and Logan’s Run, depicted bleak, dystopian futures. In addition, Hollywood simply couldn’t afford to make the kind of financial gambles that they had been able to do in the mid-1960s. It wasn’t until 1977, when Columbia Pictures invested a large portion of their assets into Stephen Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind that the idea of alien encounters was again portrayed in a serious context by a big-budget science fiction movie. The financial success of that film and Star Wars, however, firmly established the “sci-fi blockbuster” as a Hollywood staple. Although most science fiction movies made since the late Seventies have been “popcorn” action films, some notable exceptions, like Alien, Blade Runner, Contact, and Interstellar have proved that that big-budget “serious” science fiction can still be commercially successful.

Home Video

During the 1980s, 2001 was available almost exclusively on home video or television. As multiplex theaters grew in popularity, only a small handful of Cinerama theaters remained. The number of films shot entirely in 70mm after 1972 dwindled to near zero. Although some theaters occasionally rented prints for special showings, the number of people who got to experience 2001 in a theatrical setting was very small. Before 1988, all versions of the film on home video and laserdisc were in the cropped “pan and scan” format. Having been filmed in widescreen format with a 2.2:1 aspect ratio, this meant that most viewers were missing up to 40% of the picture on their TV screens. Although the Voyager Company released a letterboxed laserdisc version in 1988, it was not until 1993 that Turner Entertainment (who had purchased the rights to most of MGM’s pre-1970 titles) released the definitive letterboxed version of the film on laserdisc and videocassette for its 25th anniversary. Most people who have seen 2001 in a theater agree, however, that even the highest-resolution letterboxed video presentation, however, does not even come close to replicating the experience of seeing the film in its original Super Panavision format. As one fan of the film said, “It doesn’t come across on a television screen at all. I’ve seen it a few times since 1968 in a theatre, and many times on TV, but even on HBO with letterboxing and no commercials, it’s still just a shadow of what it is in the proper theater setup.”[75]

In the 1980s and early 1990s, 2001 was marketed to videophiles in the hope that they would purchase laserdisc players. George Feltenstein, the MGM/UA senior vice-president, said in a Variety article about the 25th anniversary laserdisc release, “Anyone who goes into a video story to purchase 2001 probably has some technological interest. They are a prime opportunity to become laserdisc owners.”[76] 2001 was released on DVD in August 1998, and on high-definition Blu-ray disc in 2007.

2010

Although Arthur C. Clarke had initially said that there would be no sequel to 2001, in December 1982 he published a novel entitled 2010: Odyssey Two. Written more as a sequel to the film than to the novel, it tells the story of a Soviet space flight to Jupiter nine years after the original voyage of the Discovery. Three Americans accompany the Russians; Heywood Floyd, the disgraced former head of the National Council of Aeronautics, Dr. Sivasubramanian Chandrasegarampillai, the programmer of the HAL 9000, and Walter Curnow, a space engineer. Arriving shortly before the Russian-American mission, a Chinese spacecraft sets down on Jupiter’s moon Europa, where they discover a life form that destroys their vessel. At the Discovery, the Americans reactivate the HAL 9000, and learn that it malfunctioned due to human error. Forced to decide between its instructions to keep secret the discovery of the original lunar monolith and its instructions to provide the crew with accurate information, the computer became paranoid and tried to eliminate the human element from the equation. Meanwhile, the ghostly specter of Dave Bowman appears to Floyd, warning him that he must leave Jupiter space within fifteen days. Using the remaining fuel in the Discovery and piggy-backing it onto the Russian craft, they return home as Jupiter is miraculously turned into a small star by the monolith, presumably to allow life to evolve on Europa.

The book was an instant best seller, scaling to the top of the New York Times bestseller list, and selling over 2 million copies over the next 15 years. Nominated by the World Science Fiction Convention for a Hugo award, the novel received moderately favorable reviews, although some complained about its amount of exposition. The New York Times reviewer wrote, “the sequel violates the mystery at every turn. We learn what the slabs are up to – and although the answer involves some splendid science-fiction conceits, it is hardly awe-inspiring.”[77]

2010 was made into a movie entitled 2010: The Year We Make Contact, co-written by Clarke and directed by Peter Hyams. It starred Roy Schieder as Heywood Floyd, with Keir Dullea and Douglas Rain reprising their roles from the first film as Dave Bowman and the voice of the HAL 9000. Although the film opened with stills and music from 2001, it was a very different film than its predecessor. A straightforward narrative, with a typical Hollywood structure, 2010 left almost nothing open to interpretation. As one reviewer said when comparing the two films,

Kubrick would often let several minutes go by in 2001 without a word of dialogue intruding; Hyams seems uncomfortable with silences. In The Year We Make Contact we never stop hearing human voices, especially Roy Sheider’s. And whereas Kubrick provides nearly no clues for us to decipher his enigmas, Hyams filled his soundtrack with voice-over explanations of events and their political import. Hyams removes most of those enigmas which might leave his audience uncomfortable or uncertain of his meanings.[78]

For the most part, the plot of the film remained true to Clarke’s novel, although Hyams added a much stronger Cold War subplot, bringing the U.S. and Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war. When the monolith turns Jupiter into a star, it has the added effect of bringing peace to the troubled Earth. 2010 ends on a very unambiguously optimistic note.

2010 was moderately successful, but it was not a hit film. Where it did achieve landmark status is in its early use of paid corporate product placements. Mark Crispin Miller quotes Advertising Age magazine’s exultation that “2010 is a case of how product placements in the movie are becoming a springboard for joint promotions used to market films.” About twenty different companies, including Adidas, Panasonic, Apple Computer, and Sheraton Hotels, are acknowledged in the closing credits, and one scene taken directly from 2001 is even featured in the film as a TV commercial for Pan Am airlines. Contrasting these with the sardonic usage of corporate logos in 2001, Miller decries the “insane revisionism” of 2010 as a film that turned the cynical outlook of 2001’s dehumanized future into a glorification of technology and corporate domination.[79] While the use of product placements in the earlier film were seen as something that was supposed to be threatening, in the later film they were seen as an indication of its realism.

2061

Having “decided not to wait” after the Challenger disaster for additional scientific information about Jupiter from the grounded Galileo spacecraft, Clarke published a new sequel, 2061: Odyssey Three, in December 1987.[80] Heywood Floyd, now 103, takes a luxury space cruise to Halley’s Comet, which has once again entered the inner solar system. Meanwhile, another spaceship is stranded on the surface of Europa, where a gigantic diamond mountain ejected from the core of Jupiter has disturbed the native life. The Europan monolith, which has now incorporated the essence of astronaut Dave Bowman and HAL 9000, is trying to deal with the question of whether or not life on the Jovian moon was worth sacrificing the possibility of life on the gas giant. The novel is structured mainly as an adventure story, and the spiritual and religious elements of the narrative are almost non-existent.

Although it achieved bestseller status, 2061 was not as successful as its predecessors were. The New York Times called it “a pallid sequel to 2010: Odyssey Two, which was a pallid sequel to Mr. Clarke’s splendid 2001. The new novel has no characters of interest, generates virtually no narrative tension and barely touches on the enigmatic monoliths that figured so prominently in the previous books; rather than resolving anything, the ending is a shameless come-on for Odyssey Four.”[81]

Internet Revolution

During the early 1990s, personal home computers and the Internet rapidly became part of the reality of many American households. Between January 1990 and January 1997, the number of people using the Internet jumped from 1.2 million to over 57 million.[88] The coming of a new electronic culture drew some comparisons to 2001 from industry journals and magazines. A 1992 article about the future of interconnected computer networking telephony argued that “HAL, the omniscient, monolithic and ultimately amoral computer from 2001: A Space Odyssey has yielded to the Borg, the interconnected, bioelectronic and ultimately amoral race from Star Trek: The Next Generation.”[89] It is important to note that even at this late date, HAL was still seen as a fundamentally flawed device, just as it was to IBM back in the 1960s. Over the next five years, popular perceptions of HAL would shift dramatically.

The rapid spread of the Internet spawned dozens of World Wide Web fan sites devoted to 2001. Although sites devoted to Star Wars and Star Trek appeared as early as 1993, it was not until 1996 that most 2001 fan pages burst onto the Web. Initially drawing traffic as repositories of HAL 9000 sound files, which many people use to customize the system sounds on their personal computers, some fans began to use their Web sites as places to publicize essays they had written about the film’s meaning. Most, not surprisingly, viewed the film in terms of technology, and nearly all expressed the view that HAL was not inherently flawed, that it was instead bad instructions from his human programmers that caused him to kill. Most of these interpretations rely on Clarke’s books and the film 2010 to make their point. Phil Vendy, who ran one of the leading 2001 fan sites of the 1990s, argued that “HAL is often cast as being the ‘Bad Guy’ or the ‘Villain’ of the film. I don’t think that this is accurate. HAL was simply trying to obey the instructions given to him and interpret them as best he could. That those instructions were was not the fault of HAL. Instead it was the fault of those who assumed that an artificial intelligence could lie in the name of security and national interest as easily as a human.”[90] Similarly, another essayist wrote, “we must understand that the malfunction was not brought by any imperfections in HAL himself, but were due to clandestine machinations by governmental forces.”[91] Using this theory, which comes straight out of Clarke’s novel, HAL is in fact more “perfect” than human beings are, because he cannot lie or deceive. Whereas Kubrick’s film suggests that HAL is flawed because he has so many human traits, in Clarke’s vision HAL is a technologically perfect victim of human greed.

3001

In March 1997, Arthur C. Clarke published 3001: The Final Odyssey. A national bestseller, the book was his most successful since 2010. It resurrects Frank Poole, one of the astronauts killed by HAL in 2001. He is discovered floating beyond the orbit of Neptune and taken to a tower reaching 20,000 miles up from the Earth’s surface where he is revived and gradually introduced to life in the 31st century, which is full of fantastical technological wonders. Eventually, he makes his way to the surface of Europa, and makes contact with the combined entity of Dave and HAL (the novel refers to them as “Halman”). He learns that the monolith is not sentient, but that its function is to report on the development of life in the solar system to the nearest “relay station” 450 light-years away. Concerned that the monolith’s superiors might destroy Earth after learning of the barbarism of the 20th century, Poole and his compatriots develop a “Trojan Horse” out of computer viruses that had been locked up on the far side of the Moon. Unleashing these upon the monolith with the help of Halman, they make all of the monoliths in the solar system disappear. The essence of HAL and Dave is preserved on a super-high memory computer chip.

Much like Clarke’s 1975 novel, Imperial Earth, 3001 is filled with detailed descriptions of a future society where nearly all of mankind’s problems have been solved by technology. At one point, the “barbarian” Poole makes a comment that the human race has deteriorated since his time, to which one of his caretakers replies, “That may be true – in some respects. Perhaps we’re physically weaker, but we’re healthier and better adjusted than most humans who have ever lived. The Noble Savage was always a myth.”[82] The last 20 pages list the numerous sources that Clarke drew upon for the scientific ideas in the book.

Most critical reviews of 3001 were mixed. A New York Times review by mathematician John Paulos, said, “The plot…hangs together reasonably well, although in this third and – the subtitle would suggest – final sequel to 2001, Mr. Clarke has to struggle to weave all the threads into a coherent narrative.”[83] Most reviewers complained about the book’s literalness and lack of spirituality. The Economist’s review compared 3001 with 2001, saying “In “2001“, the monoliths were doors of transcendent perception; in “3001” they become banal and easily dealt with alien threats. Poole’s avenger, David Bowman, is the Odysseus transformed at the end of 2001 into a “star child” of seemingly unlimited potential; in 3001 he is just one more sentient computer program.”[84] Another New York Times review by Richard Bernstein read, “Mr. Clarke’s new book…is full of whimsy about the world of the future. But it is so languid and unmysterious, so lacking in the elaboration of plot, character or concept, that it reads more like a proposal for itself than like a fully realized work.”[85]

Clearly, financial interests played a role in the writing of 3001. Clarke was given a $2 million advance from was the advance of Ballantine Books, a previously unheard of sum for a science fiction writer. Clarke is said to have commented, “They waved a lot of greenbacks at me until my eyes glazed over”.[86] The investment paid off, however, as 3001 spent ten weeks at the top of the New York Times best-seller list, peaking at number two in the spring of 1997.[87]

HAL’s “Birthday”

In January 1997, many fans celebrated the “birthday” of HAL 9000. According to the film, 2001’s super-intelligent computer was first activated on January 12, 1992, although Arthur Clarke chose the year 1997 for his book. Except for a small item that went out on the Associated Press newswire and an article in the New York Times, the 1992 date passed quietly.[92] The Times article referred to 2001 as “Clarke’s film” and neglected to mention Stanley Kubrick even once, instead focusing almost entirely on efforts by computer scientists to make an intelligent computer like HAL.[93] For the 1997 date, however, many diverse media sources did articles on HAL and how close modern science was to achieving the “vision” presented in the film.

A book entitled HAL’s Legacy: 2001’s Computer as Dream and Reality was published containing essays edited by MIT professor David Stork from experts in the field of computer science and technology on the practicality of different aspects of the computer’s design and features. A fan of the film who has seen it at least 30 times, Stork presented two different theories for the discrepancy in the two dates for HAL’s inception. In an early 1997 article, he contended that actor Douglas Rain “thought that 1997 was so ridiculously far into the future that he mistakenly read it as 1992.”[94] In the introduction to his book, he suggests that Kubrick changed the year to 1992 to make HAL’s death “more poignant.”[95] Stork explicitly states the question that runs throughout the book in the first chapter, “As we approach 2001, we might ask why we have not matched the dream of making a HAL.”[96]

Wired magazine ran a 13-page cover feature on HAL 9000 in January 1997. Leaving behind all mention of the film’s spiritual or sociological interpretations, the article instead focused entirely on the “promise” presented by 2001’s vision of a technological future. The article argues that the question audiences should ask is not how close 2001 came to predicting the technology of the future, but instead, “how close today’s computers are to realizing the promise of HAL. When will 2001’s dream become reality?”[97]

In March of 1997, film critic Roger Ebert presided over “Cyberfest ‘97”, a gala celebration at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In both the film and novel version of 2001 Urbana, Illinois is the location of the plant where HAL was activated. The weeklong event featured lectures and talks on the history of computing, the making of 2001, demonstrations of cutting-edge research at the University of Illinois, and appearances by people such as 2001 design consultant Harry Lange. During the event’s final evening, Arthur Clarke (who had just published 3001) even made an appearance via “cybercast” from his home in Sri Lanka, as part of a panel that included David Stork and 2001 actor Gary Lockwood. Financed by corporate sponsors such as Apple, Microsoft, Ameritech, Oracle, and Lotus, the celebration also helped showcase the latest technological achievements of these companies. When contacted by Roger Ebert and invited to the gathering, Stanley Kubrick’s only response reportedly was that “HAL was born in 1992, and if you didn’t have a birthday party then, it’s too late to have one now.”[98]

For most of the people celebrating HAL’s birthday, the computer represented the triumph of technology. Believing in the vision of 2001’s technology, and regarding HAL as a “perfect” machine rather than Frankenstein’s monster, these people, like the film’s early critics, did not necessarily see the film in terms of its satirical undertones. A perfect example of this reassessment is the changing attitude that IBM had toward HAL. Having initially been upset by the use of their corporate logo in a film that featured a computer that killed several people, the company was further angered when they discovered that the letters H, A, and L are only one letter removed from I, B, and M in the alphabet. Clarke, who said the letters stood for “Heuristically programmed Algorithmic computer” spent many years attempting to dismiss the rumor that this had been done intentionally, claiming as early as 1972, “we were quite embarrassed by this, and would have changed the name had we spotted the coincidence.”[99] Despite having gone to the trouble of having Dr. Chandra deny the connection in 2010, by 1997, Clarke acknowledged that the original inspiration for the name had come from Kubrick.[100] In the closing notes to 3001, he noted that, “far from being annoyed by the association, Big Blue is now quite proud of it.”[101] After years of distancing themselves from 2001, IBM now embraced the “reformed” HAL.

Commercial Co-Option

Mark Crispin Miller has argued that is just this kind of corporate co-option of 2001 that has helped to conceal the satiric impact of the film. In a 1994 article for Sight and Sound magazine he stated that “as such colossal advertisers have absorbed the culture since the early ‘70s, they have helped obscure 2001 by celebrating and encouraging the very drives Kubrick satirizes.” Thus, the plethora of conscious references to 2001 and the glorification of HAL in the mass media gains an added dimension of irony. In the 1996 hit film Independence Day, Jeff Goldblum’s character uses a computer with HAL’s voice and image to save the Earth from alien destruction. HAL had gone from representing the menace of technology to a symbol of how it can save the human race. Miller argues that most audiences would not respond to 2001 if it were to be re-released in theaters today, because the film “would be diminished by the multiplex not just because of the smaller screen and poor acoustics, but because the very setting would implicitly subvert the film’s subversive vision.[102] Warner Brothers, who currently owns the distribution rights to 2001, planned an international re-release of the film in the year 2001. Although studio executive Barry Reardon wanted to add digital effects to the film, plus some of the footage cut out of the original release, this idea was rejected by Kubrick, who completed supervision of the film’s digital remastering before his death in March 1999. The subsequent re-release was limited to art house theaters.

The AFI Brings It All Together

The American Film Institute’s seminar celebrating the 30th anniversary of 2001 in April 1998 brought together people representing a wide range of views about the film. Arthur Clarke, again appearing via satellite, joined the talk eleven minutes late due to technical difficulties. David Stork was there, as well as 2001 actors Keir Dullea and Gary Lockwood. Tom Hanks and astronaut Bill Anders were also a part of the panel, which was moderated by science writer Andrew Chaiken. Each one of these people brought their own recollections and interpretations to the panel, sharing them with the audience. Arthur Clarke at one point complained about Kubrick’s “unrelenting perfectionism” and the “rather pessimistic view of humanity” seen in 2001 and his other films. Gary Lockwood entertained the audience with his stories of friends who dropped acid while watching the film. Tom Hanks compared his first viewing at the age of 12 to “seeing Monet’s ‘Water Lilies’ or Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘La Gioconda’” in that it allowed him to understand concepts without words. David Stork argued that the only thing missing from 2001 “is for scientists to fill in the stage set with the real technology.” But it may have been Keir Dullea who tapped into the real reason that the film continues to have such a wide appeal:

It resonates in people because it touches on the instant our wonder – not only our wonder about space, but our wonder about time, our wonder with our relationship to the Deity perhaps – because you get as many interpretations of what the film means as you do almost people who have seen it. That’s true of almost any great work of art – if you see a Picasso, is it important to know what Picasso intended, or is it important to know what your relationship is, your emotional reaction is to it?[103]

2001 continues to generate emotional reactions within people who see it. In the 1960s it resonated in particular with a Baby Boomer audience searching for meaning in a world filled with turmoil. They were astounded by its sound and special effects, appreciated its commentary on the dangers of technology and commercialization, and inspired by its themes of spiritualism and cosmic rebirth. Older audiences and members of the critical establishment initially judged it on the basis of previously existing expectations about what a film should be, although some gave it a second chance. Arthur Clarke and Stanley Kubrick had different visions of what they felt the story was about, and although Kubrick’s movie made the first impression on many, others came to rely on Clarke’s more technology-oriented interpretation as canon. Through the early 1970s, many film critics and scholars attempted to deconstruct 2001 with varying results, although most agreed that it was some kind of cosmic satire. When the film left theaters and public consciousness during the late 1970s and the 1980s, people relied either on Clarke’s novel, or low-fidelity television broadcasts and home video. Clarke’s sequels to 2001 rewrote many of the themes in the earlier film, and in the more materialistic world of the 1980s and 1990s, they appealed to Baby Boomers and their children who were less concerned with the story’s spiritual or satirical elements as they were intrigued by its promise of futuristic technology. HAL was redeemed in Clarke’s novels and on the Internet. By his 1997 “birthday” even IBM was willing to take him back. 2001 was no longer seen as “The Ultimate Trip”; it was once again “An epic drama of adventure and exploration.”

New theatrical prints of 2001 have been struck several times since 1999, accompanied by limited theatrical releases, where it continues to attract sell-out crowds. 2001 has consistently demonstrated its ability to appeal to multiple generations and hold its own next to more fast-paced sci-fi adventures for nearly half a century. Roger Ebert’s prediction that 2001 will still be familiar to audiences 200 years from now appears well on its way to coming true.